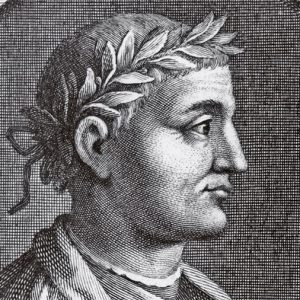

Francesco Petrarca, better known as Petrarch, died on 19 July 1374. He left behind poetry, prose and ideas that helped shape modern literature. Born in Arezzo in 1304, Petrarch became one of the most important figures of early humanism. Today, he is remembered not only for his beautiful verse but also for his influence on writers such as Shakespeare.

Petrarch’s life spanned a time of great upheaval in Italy. The peninsula was divided into city-states, with power struggles between the Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire. The Church, based in Avignon during much of Petrarch’s life, faced growing criticism. Meanwhile, scholars began to rediscover classical texts, laying the groundwork for the Renaissance. Petrarch stood at the centre of this intellectual shift.

Educated in Avignon and later in Bologna, Petrarch originally trained as a lawyer. He soon abandoned law for a life devoted to letters. He found inspiration in the works of Cicero, Virgil and Augustine. Their influence helped form Petrarch’s belief that classical learning could enrich Christian thought. This view would later define Renaissance humanism.

Petrarch and his Canzoniere

Petrarch is best known for his poetry, especially the Canzoniere – a collection of over 300 poems written in Italian. Most are sonnets, and most focus on a woman named Laura, whom he claimed to have seen for the first time in 1327. Laura may have been a real person or a literary invention. Either way, she became a symbol of ideal love and unreachable beauty.

These poems shaped the sonnet form and set a model for future poets. Petrarch’s use of language, rhythm and personal emotion was revolutionary. He combined classical restraint with deep feeling, giving voice to both passion and inner conflict. His sonnets helped shift poetry from public themes to private experience.

Though Petrarch wrote in Italian, he also valued Latin as the language of serious thought. He composed letters, essays and dialogues in Latin, including Secretum, a fictional conversation with Saint Augustine. In it, Petrarch explores his spiritual struggles and desire for fame. He also wrote biographies of famous men in De Viris Illustribus and collected ancient manuscripts, preserving many that might have been lost.

Longed for a united Italy

One of Petrarch’s key political hopes was for a united Italy. He disliked the corruption of the Avignon Papacy and longed for a revival of Roman civic virtue. He called for moral reform and often criticised the Church hierarchy. Yet he remained a devout Christian. This tension between faith and reason, between action and contemplation, ran through his life and work.

Petrarch’s relationship with Dante Alighieri was complex. Though the two never met, and Petrarch was only 17 when Dante died, Petrarch was not a fan of Dante’s political stance. Dante had been exiled from Florence for his support of the White Guelphs. He wrote his masterpiece, The Divine Comedy, in exile, blending classical learning, Christian theology and biting political criticism.

Also read: On this day in history: Dante Alighieri born (possibly)

Petrarch followed a different path. He enjoyed the favour of various courts, especially in Milan and Venice. Unlike Dante, he avoided overt political involvement. Still, he valued liberty and justice, and he praised the ancient Roman republic. He saw poetry and learning as tools to improve society.

Petrarch’s influence on European writers

Dante and Petrarch both helped establish Tuscan as a literary language, but Petrarch’s influence on later poets was broader. His sonnets became models for writers across Europe. In England, Sir Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, adapted his style in the early 1500s. Their work laid the foundation for the English sonnet tradition.

No poet absorbed Petrarch’s influence more deeply than William Shakespeare. Many of Shakespeare’s sonnets echo Petrarchan themes: unrequited love, time’s cruelty, the power of verse to preserve beauty. Shakespeare also used the sonnet’s formal structure but adapted it to his own language and concerns. Where Petrarch’s love for Laura remained distant and idealised, Shakespeare’s subjects often appear more earthy and real.

By the time of his death in 1374, Petrarch had become famous throughout Europe. He received honours from kings and popes and was crowned poet laureate in Rome in 1341. Yet he remained, at heart, a solitary thinker. He often wrote about the passing of time and the fleeting nature of earthly fame.

Petrarch’s legacy is vast. He helped revive interest in classical antiquity, encouraged the use of the vernacular, and shaped poetic form for centuries. More than that, he gave future writers a model of introspective, emotionally rich expression.

In a world torn by war, plague and political chaos, Petrarch looked back to the past for guidance but also ahead to new ways of thinking. His blend of classical learning, Christian belief and poetic beauty helped spark the cultural rebirth we now call the Renaissance.