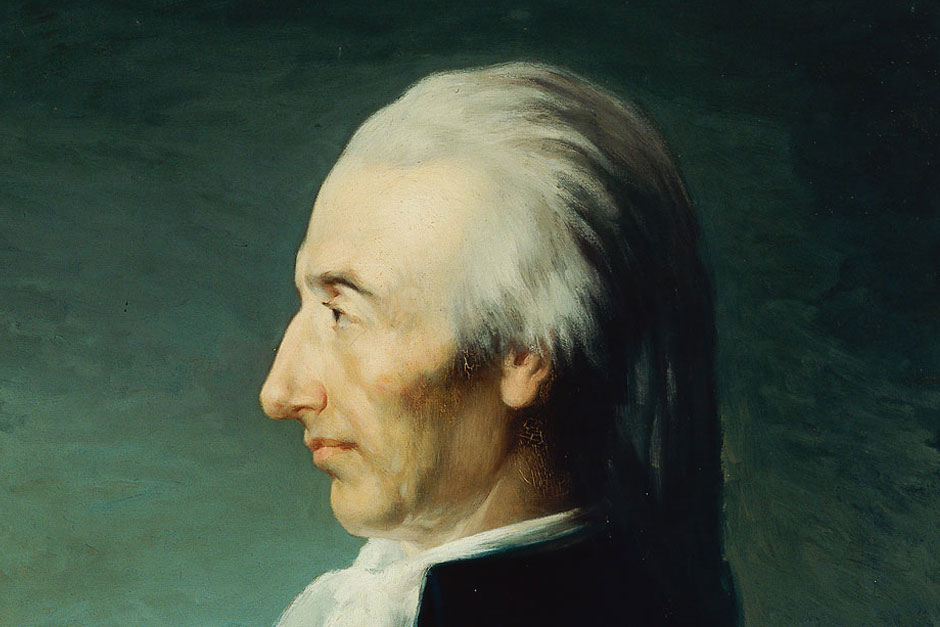

Alessandro Malaspina, one of Italy’s greatest but least celebrated explorers, was born on 5th November, 1754 in Mulazzo, a small village in northern Tuscany. Though his name is far less famous than Columbus or Vespucci, his achievements as a navigator, scientist and cartographer were equally significant.

Malaspina’s work under the Spanish crown advanced global geography and deepened understanding of the Pacific world during the Enlightenment.

After serving as an officer in the Spanish navy, Malaspina proposed a major scientific expedition to rival those of James Cook and the Comte de La Pérouse. The Spanish government, eager to assert its imperial influence and expand its knowledge of the Pacific, approved the plan. In 1789, Malaspina set sail from Cádiz at the head of two purpose-built ships, the Descubierta and the Atrevida. Over nearly five years, his crews explored and charted vast stretches of the Pacific, combining navigational precision with scientific inquiry on an unprecedented scale.

Pacific expedition

The expedition followed the western coasts of South and North America, from Cape Horn to Alaska. In the Gulf of Alaska, Malaspina’s team carried out detailed hydrographic studies and conducted ethnographic research among the Tlingit people. The explorers gathered plants, animals and cultural artefacts, recording them with the help of artists and naturalists who travelled on board. Their work confirmed that no navigable Northwest Passage existed in that region, contradicting popular European myths of the time.

From the icy shores of Alaska, Malaspina’s ships turned south toward the Spanish outpost of Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island, where they mapped and described the local environment in greater detail than any expedition before them. They later surveyed the mouth of the Columbia River and sailed on to Acapulco, before crossing the Pacific to explore the Philippines, New Zealand and the east coast of Australia. The expedition returned to Spain in 1794, having completed a circumnavigation that rivalled the best scientific voyages of the century.

Promotion and downfall of Alessandro Malaspina

Malaspina’s findings were extensive. His charts corrected earlier errors, his astronomical measurements refined navigation techniques, and his natural history collections enriched scientific understanding across Europe. He also wrote critically about Spanish colonial administration, arguing for reforms and better treatment of indigenous populations — views that reflected Enlightenment ideals but ultimately led to his downfall.

Upon his return, Malaspina received praise adn promotion. However, political tensions in Spain soon turned against him. Accused of involvement in a conspiracy to depose the prime minister, he was arrested, stripped of his rank, and imprisoned for eight years. The authorities confiscated his massive archive of journals, drawings and specimens, and his planned seven-volume account of the expedition remained unpublished for nearly two centuries.

Malaspina was finally released through the intervention of Napoleon Bonaparte but never recovered from the years spent in confinement. He returned to Italy and settled in Pontremoli, where he died in 1810 at the age of 55. His reports were eventually rediscovered and published in full between 1987 and 1999, revealing the extraordinary depth and breadth of his scientific work.