Collectors can now buy certified digital copies of major Italian artworks. Cultural officials launch a project that promises museum-quality reproductions for a fraction of the cost of an original.

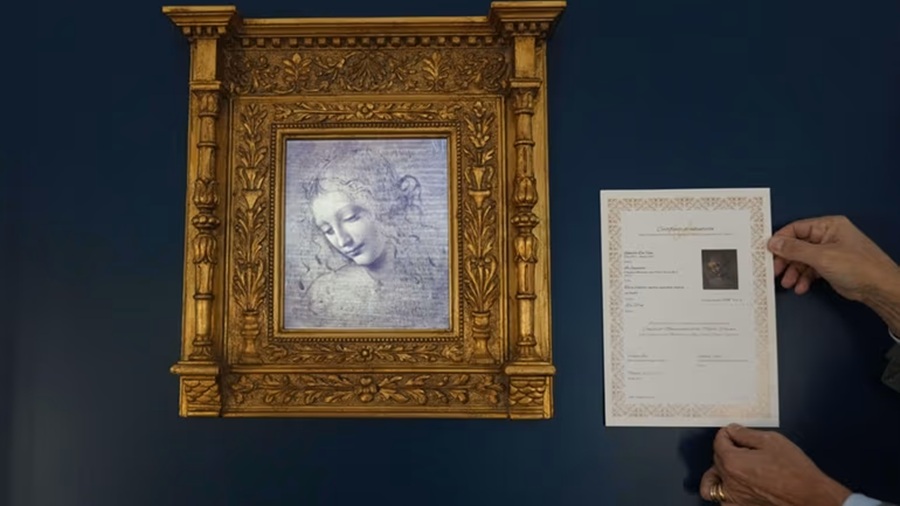

The initiative, run by the nonprofit Save the Artistic Heritage with its technical partner Cinello, offers high-end buyers a chance to own a life-size projection of masterpieces such as Leonardo’s Lady with Disheveled Hair. Each edition is framed and scaled to match the original, creating an experience close to a museum display.

Participating museums sign certificates of authenticity and receive 50 percent of the profits. Prices range from €30,000 to €300,000, with revenues helping institutions boost funding at a time of tight budgets. The project has already delivered €300,000 to Italian museums over the past two years.

Limited series of nine

The digital pieces are produced in limited runs of nine. This echoes the traditional number of casts permitted from a single mould while still being considered original. The catalogue includes around 250 works from ten Italian museums and foundations. These include Milan’s Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Naples’ Capodimonte and Parma’s Pilotta. The Pilotta owns Leonardo’s unfinished painting of a woman with windblown hair, which the digital programme sold for €250,000.

John Blem, founder of Cinello and vice president of the nonprofit, said the aim was to create artworks rather than technology. He emphasised the project’s role in offering museums new income streams. A similar nonprofit will launch in the United States next year.

Digital displays that mimic originals

The digital copies appear as backlit images on screens built to the same size as the originals. Brightly coloured works, such as Raphael’s The Marriage of the Virgin displayed at Milan’s Brera Art Gallery, gain an added sense of luminosity. More subdued paintings, including Leonardo’s portrait and Mantegna’s Lamentation over a Dead Christ, retain visible detail down to individual brush strokes. The one thing missing is the texture of the original surfaces.

Brera director Angelo Crespi said the Raphael reproduction had generated strong interest. He praised its clarity and colour but noted viewers could still tell it was a digital screen on close inspection.

Digital technology is becoming increasingly common in the art world, with museums experimenting with digital canvases, high-resolution scans and immersive experiences. The Van Gogh Museum has trialled 3D scans and global interactive exhibitions. Meanwhile Italian institutions have long used high-quality copies for preservation and fundraising.

Supporting museum budgets

Italy’s Brera Museum has launched a second series of nine digital works with Save the Artistic Heritage. These new pieces will help attract donors and support promotional campaigns.

The Brera relies on donations, sponsorships and projects for 30% of its €14 million annual budget, with only 10% coming from the state. Ticket sales cover the rest, making new revenue sources essential.

The digital works use Cinello’s patented system: a replica frame houses a screen linked to a secure box that contains the unique digital file. The artwork displays only when the device connects to Cinello’s mainframe, ensuring each copy remains authenticated and singular.

“Save the Heritage is not just making a sale,” Crespi said. “They are creating a system that allows any buyer to support the museum.”